Crowdsourcing can be defined as “the practice of obtaining needed services, ideas, or content by soliciting contributions from a large group of people and especially from the online community rather than from traditional employees or suppliers” (Merriam Webster 2019).

In relation to crowdsourcing in terms of disaster relief, Mark Riccardi’s journal article on this subject (2016) further defined crowdsourcing as “using the power of the Internet and social media to “virtually” harness the power of individuals and bring them together in support of a disaster”.

The term crowdsourcing was first used by journalist Jeff Howe in 2006 (Ghezzi et al 2017). However, one of the first recorded examples of crowdsourcing dates backs as far as 1714 when the British government, through the Longitude Act 1714, offered a £20,000 reward for a tool that could accurately measure longitude and thereby improve maritime safety and reduce the number of sailor’s lives lost. This led to the invention of the first marine chronometer (Dunn 2014).

Today, the affordances offered by the internet and social media networks means that awareness of issues and natural disasters can be quickly broadcast around the world with a vast array of tools available to digital citizens to solicit assistance and solutions.

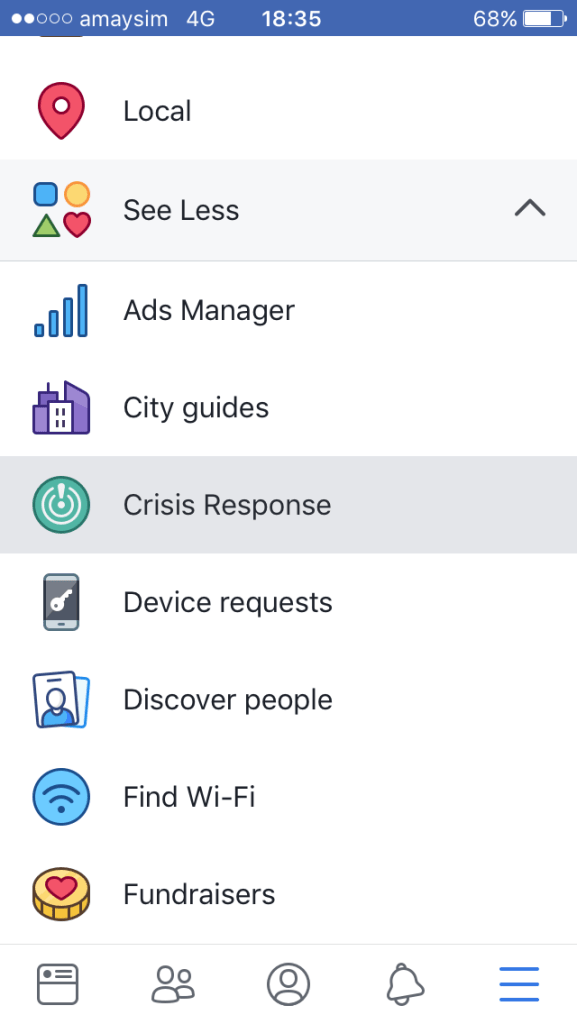

Facebook has been developing crisis response tools since the 2011 tsunami and earthquake in Japan. Starting with a message board and evolving to the launch of their Safety Check tool in 2014. They then expanded this to Community Help and Fundraisers. In 2017, Facebook combined all of these affordances into a single resources called Crisis Response Centre (Nowak 2017).

“Crisis Response lets people affected by crises tell friends that they’re safe, find or offer help, and get the latest news and information” (Facebook 2019).

Unfortunately, poor data collection and access to credible information can negatively impact on humanitarian and emergency efforts during times of crisis. However, crowdsourced crisis mapping can assist efforts by plotting data and hotspots, enabling the analysis and planning of effective strategies. Some of the most notable crisis mapping organisations and software tools include: Standby Task Force, Crisis Mappers, Crisis Commons, Digital Humanitarians Networks, Ushahidi, Google Crisis Response and UN Global Pulse (Skuse 2019 pp. 1-9).

In the wake of the devastation of #hurricaneDorian2019 across the #Bahamas Standby Task Force, a group of crisis mapping volunteers, compiled data on the status of medical clinics and hospitals in the Bahamas. According to DirectRelief.Org, mapping has provided first responders with invaluable insights into population movement during the emergency and access to medical clinics and supplies (Smith 2019).

Research on crowdsourcing efforts from earthquakes and hurricanes in Haiti, wildfires across Colorado and flooding in Pakistan has shown that crowdsourcing enables emergency managers to more efficiently prioritise and coordinate resources and volunteers. Through our global connectedness online, crowdsourcing has proved to be a powerful and effective tool to raise awareness of crisis situations and attract resources (Riccardi 2016 pp. 123-127).

References:

Crowdsourcing, Merriam Webster, 2019 <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/crowdsourcing>.

Dunn, R, 2014, The History, Longitude Prize.Org, <https://longitudeprize.org/about-us/history>.

Ghezzi, A, Gabelloni, D, Martini, A, & Natalicchio, A, ‘2017, Crowdsourcing: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research’. International Journal of Management Reviews. 10.1111/ijmr.12135.

Nowak, M, 2017, ‘A New Center for Crisis Response on Facebook’, Facebook Newsroom, September 2017, <https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/09/a-new-center-for-crisis-response-on-facebook/>.

Skuse, A, 2019, ‘Crowdsourcing and Crisis Mapping in Complex Emergencies’, Australian Civil-Military Centre or the Australian Government, May 2019, This paper is published under a Creative Commons license, <https://www.adelaide.edu.au/accru/projects/ACMC2/Crowdsourcing_and_Crisis_Mapping_Final_ISBN.pdf>.

Riccardi, M, 2016, ‘The power of crowdsourcing in disaster response operations’ International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol 20, pp 123-128.

Smith, N, 2019, ‘In Hurricane Dorian’s Wake, Maps Provide Essential Insights for First Responders’, DirectRelief.Org, August 2019, <https://www.directrelief.org/2019/08/in-hurricane-dorians-wake-maps-provide-essential-insights-for-first-responders/>.

Images:

Crisis Response Infographic, [image], in Facebook Newsroom, 2017, <https://fbnewsroomus.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/crisis-response-infographic.png>.

Crisis Response Screenshot [image], Facebook App, 2019.

Volunteer Hands [image], in Pixabay, Gerd Altman 2019, <https://pixabay.com/illustrations/volunteers-hands-voluntary-help-4021489/>.